This is a Plain English Papers summary of a research paper called QE4PE: Word-level Quality Estimation for Human Post-Editing. If you like these kinds of analysis, you should subscribe to the AImodels.fyi newsletter or follow me on Twitter.

Overview

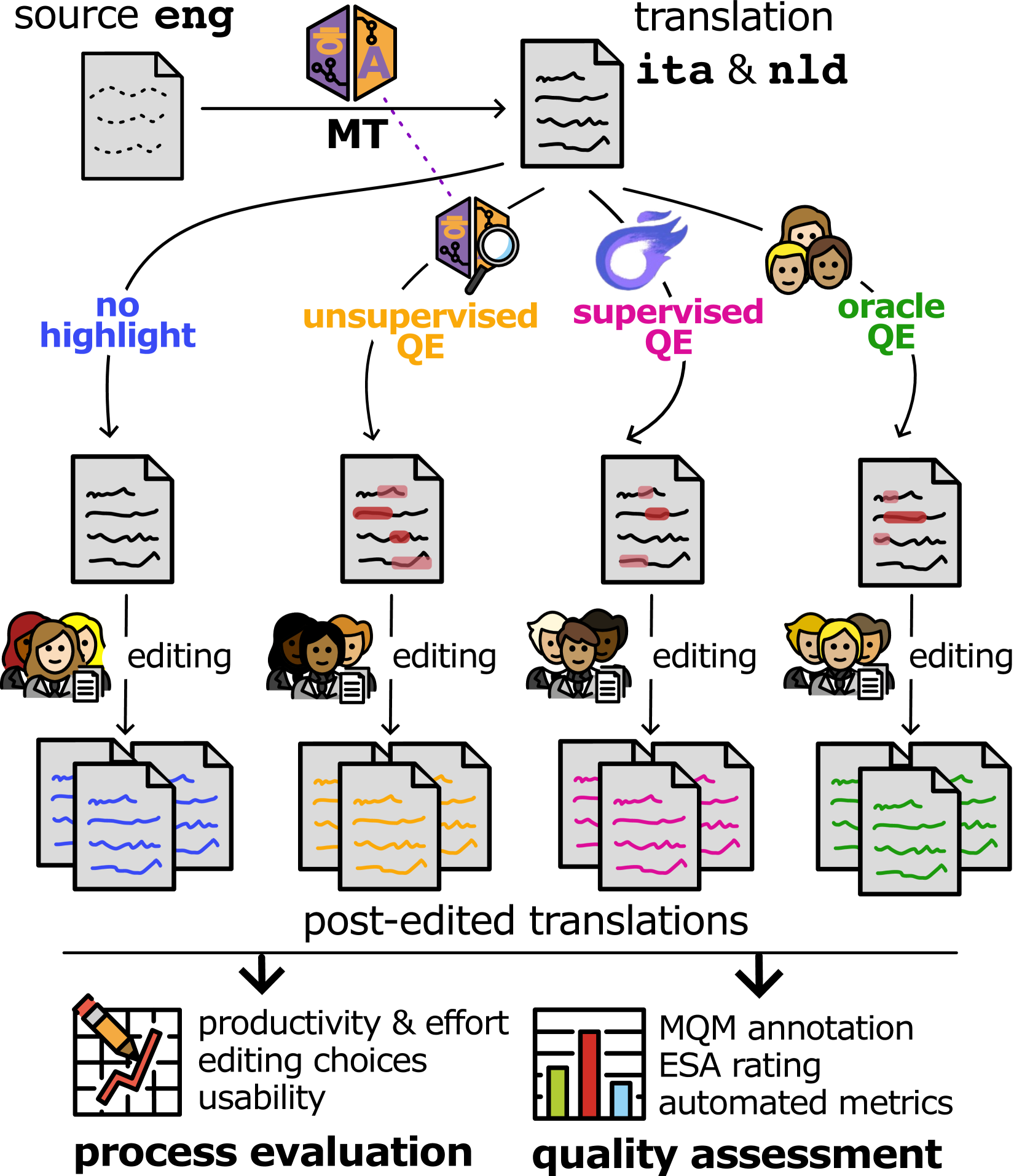

- QE4PE introduces a word-level quality estimation system specifically for human post-editing of machine translations

- System predicts which words in machine translation output need editing by humans

- Uses a two-stage approach: first trains on synthetic data, then fine-tunes on real human post-edits

- Achieves significant improvement over baseline models in predicting necessary edits

- Focuses on practical applications rather than just academic metrics

- System reduces post-editing effort by 12-30% based on real-world testing

Plain English Explanation

When a machine translates text from one language to another, it often makes mistakes. Currently, human translators fix these mistakes in a process called "post-editing." This is time-consuming and expensive.

The researchers built a system called QE4PE that predicts which words in a machine translation are likely wrong and need fixing. It's like having a spell-checker that highlights potential errors before a human editor even starts working.

Think of it as a smart assistant that says, "Hey, these specific words probably need your attention" rather than making a human review every single word. This quality estimation approach could save translators significant time and effort.

What makes this work different is that it focuses on practical, real-world editing patterns. Instead of theoretical perfection, it learns from how actual humans fix translations. The system was trained first on synthetic data (machine-generated examples) and then fine-tuned using real human edits, much like teaching someone basic principles first before showing them how things work in the real world.

When tested in real translation workflows, the system reduced post-editing effort by 12-30% - a substantial efficiency gain for professional translators.

Key Findings

The QE4PE system demonstrated several important results:

- The system achieves 69.9% F1 score on predicting which words need editing, significantly outperforming baseline approaches

- A two-stage training approach (synthetic data followed by fine-tuning on real edits) works better than either method alone

- When implemented in professional translation workflows, the system reduces post-editing effort by 12-30%

- The system works effectively across multiple language pairs including English-German, English-Chinese, and English-French

- Human translators found the word-level suggestions helpful and intuitive compared to sentence-level quality scores

- The system specifically addresses "edit bias" - focusing on words that humans actually change rather than theoretical errors

The researchers also found that focusing on real human editing patterns rather than abstract quality metrics resulted in more practical and useful predictions.

Technical Explanation

The QE4PE system employs a novel word-level quality estimation approach specifically tailored to predict human post-editing needs. The system architecture uses a transformer-based model with modifications to handle parallel text from source language, machine translation, and post-edited reference.

The training methodology consists of two critical stages. First, the model is trained on synthetic data generated by comparing machine translations with human references and applying automatic alignment techniques to identify edited words. This creates a large initial training dataset with word-level edit labels. Second, the model is fine-tuned on a smaller dataset of actual human post-edits, where the edit decisions directly reflect human judgment rather than automated alignment.

For feature representation, the system encodes both source text and machine translation output using cross-lingual embeddings, allowing it to capture relationships between source and target language tokens. The model outputs binary classifications for each word in the machine translation: "OK" (no edit needed) or "BAD" (requires editing).

The researchers implemented several technical innovations to address class imbalance (since most words don't need editing) including focal loss and data augmentation techniques. They also experimented with ensemble approaches combining predictions from multiple model instances.

In evaluation, the system was measured using both standard metrics (F1 score on BAD class predictions) and through integration into professional translation workflows to measure actual time savings. The latter represents a significant methodological advancement in quality estimation research, moving beyond academic benchmarks to practical impact.

Critical Analysis

While QE4PE shows impressive results, several limitations should be considered. First, the system was primarily evaluated on high-resource language pairs like English-German and English-Chinese. Its performance on low-resource languages remains untested, which is a significant gap given that translation quality tends to be lower for such languages.

The paper acknowledges but doesn't fully resolve the issue of annotation inconsistency. Human translators often make stylistic edits that aren't strictly necessary for accuracy, and different translators may edit different words even when the meaning is preserved. This fundamental variability in post-editing creates an upper bound on prediction accuracy that isn't clearly established.

The researchers also don't thoroughly explore how domain-specific content affects the system's performance. For technical, legal, or creative content, the patterns of necessary edits may differ substantially. Additionally, the system's integration with newer error annotation standards like MQM (Multidimensional Quality Metrics) is not addressed.

A more fundamental question is whether targeting human editing patterns is the optimal approach. As machine translation improves, human editing patterns will change - creating a moving target for the QE system. The paper doesn't address this evolving landscape and how the approach might adapt to improving MT quality.

Furthermore, while the system focuses on identifying words that need editing, it doesn't predict what the corrected words should be - a capability that would further reduce human effort.

Conclusion

QE4PE represents a significant advancement in bringing quality estimation technology into practical translation workflows. By focusing on predicting actual human editing behaviors rather than abstract quality metrics, the system addresses a real industry need and demonstrates tangible efficiency improvements.

The two-stage training approach provides a blueprint for other machine learning systems that need to bridge the gap between synthetic data (available in large quantities) and real-world human behaviors (available in limited quantities). This methodology could extend beyond translation to other text processing tasks requiring human refinement.

Looking forward, this work opens several promising directions. As machine translation continues to improve, quality estimation systems like QE4PE could evolve from simply identifying problematic words to suggesting specific corrections. The demonstrated productivity gains (12-30% reduction in editing effort) have significant economic implications for the translation industry, which handles billions of words annually.

Ultimately, QE4PE illustrates how AI systems can be designed not to replace human expertise but to make it more efficient by focusing human attention precisely where it's needed most - a model that could apply to many knowledge work domains beyond translation.

If you enjoyed this summary, consider subscribing to the AImodels.fyi newsletter or following me on Twitter for more AI and machine learning content.